|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

hello welcome to who will compete with spacex a talk about markets and moats. To review a little history spacex first flew the falcon 9 in 2010, they first landed a booster in late 2015 and they did their first crewed launch in 2020 so they've been really flying this booster for at least 10 years

The obvious question is where's the competition? Why isn't anybody else doing the kinds of things that spacex is doing and that's one form that this question comes up in the other form is an assertion that a specific company will be competitive with spacex as soon as they are flying without without a lot of reasons

So I thought it would be interesting to look at the sort of advantages that spacex currently has and has had along the way and do a business analysis and this is the same sort of business analysis I'd do if i was looking to invest in a company, you know if i was looking to buy their stock i want to understand what their competition is.

I'm going to start by talking about moats and motes are just a fun way to think about competition so here's a nice moat in tokyo and on the left side we have a castle and then we have a big moat in the middle and on the right side we have the other side of the moat.

In terms of this analogy the company is the castle and the competitors are off on the other side of the moat and for them to be able to compete with the company they must cross the moat to the other side, so conceptually a moat is anything, any advantage that the company has that makes it hard for competitors to compete with them.

There are different kinds of moats. some moats are big and really hard to cross; there's a lot of water there and it's really hard to get to the castle on the other side.

some moats are very easy to cross so just because there's a moat does not mean that this is a significant impediment to competing with a company so let's start by looking at existing contracts.

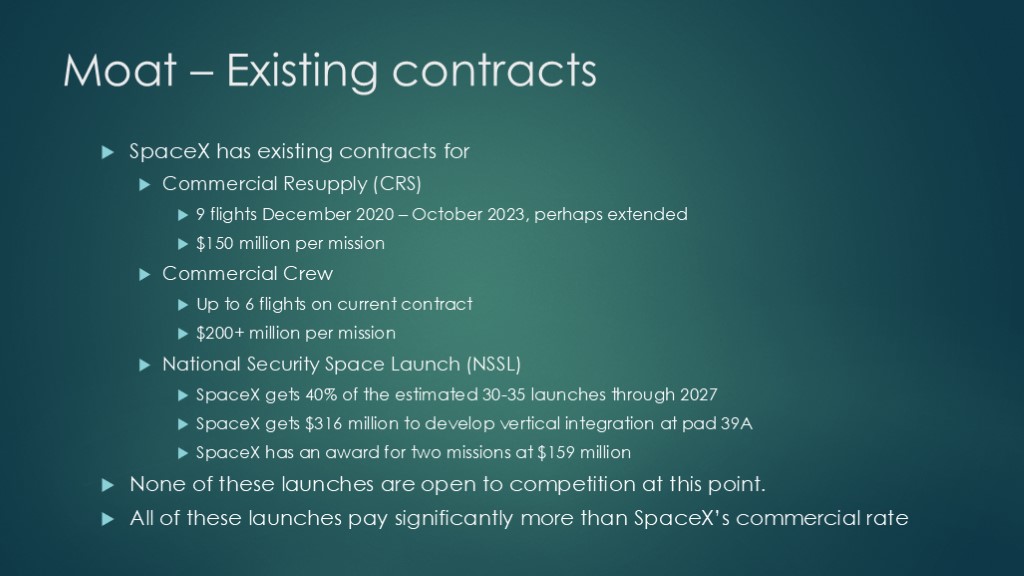

Spacex has a number of existing contracts:

they have a contract for commercial resupply of iss and that contract is for nine flights running from december 2020 so last year throughout through October 2023. That might be extended - it's likely iss will be extended so this contract might be extended or it might be a new contract at the end of that period and those are costing around 150 million per mission.

There's commercial crew - spacex in the initial contract has up to six flights we don't actually know how many nasa has chosen but it's pretty likely they've chosen six and then once again a chance for renewal after that, and those are probably 200 million plus

per mission. Obviously flying people in the crew version takes more work than flying cargo in just the cargo version.

Then finally there's national national security space launch and spacex gets 40% of these launches through 2027. ULA gets the other 60 so they were the two winners and they split up 60/40 the award, so that'll be somewhere around 12 or 15 launches as part of this award.

Spacex also got 316 million dollars to develop the ability to launch vertically integrated payloads at pad 39a - some of the NSSL payloads don't tolerate being down on their side they need to be vertical so this is the government paying spacex to build themselves a new capability so it's another nice thing that often comes with these sort of things.

Then they have an award for a couple missions kind of at the start of this time period.

None of these launches are open to competition at this point so you can add that up and there are 20 tomaybe 25 flights here that nobody else is going to fly them they will only be flown on spacex unless something weird was to happen, and with the chance of extending all ofthem and you can expect that spacex would be a significant competitor in rebids for any of these.

This is a pretty significant moat and all of these pay more than spacex's commercial rate - if you came and said to spacex i just want you to launch a satellite, it's not going to cost you this much, this kind of money. Part of that is for additional services so for the space station launches obviously they need a dragon spacecraft and that costs some money to build and refurbish and fly and for NSSL there's a lot of extra paperwork actually for both of them there's a lot of extra paperwork but still these are nice lucrative contracts.

If you want to compete with spacex you can't expect to pull any of these contracts away - they aren't launches you can compete on.

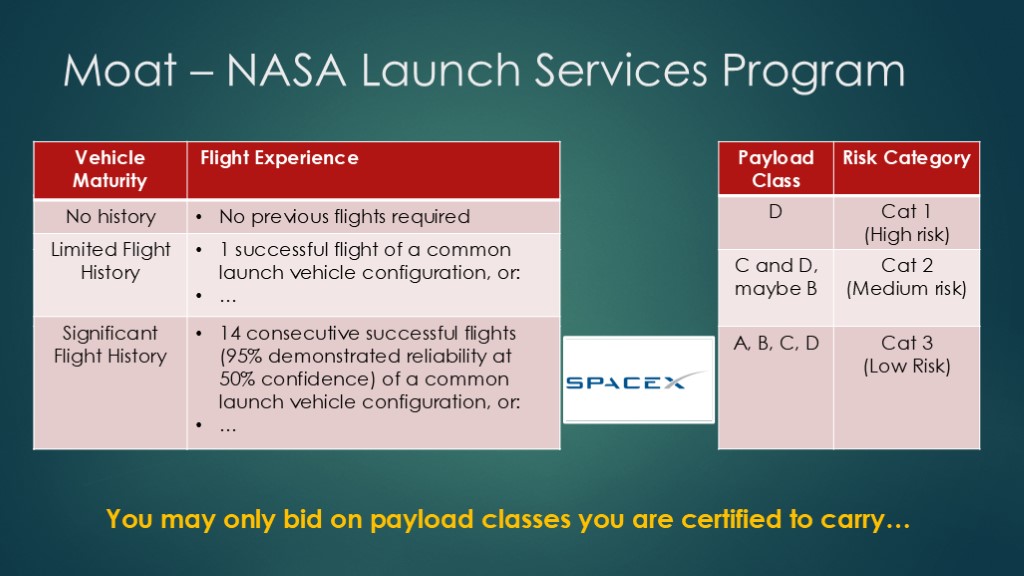

There's also what's called the nasa launch services program, and nasa categorizes launch vehicles based upon their flight history, so you can join this program and when you first join with the new launcher they'll say okay you have no history you don't have any previous fights so that's how we class you with no history.

You fly for a while and i list one of the criteria here there's actually a a long series of things that you have to do to qualify with limited flight history but you have to have flown some that puts you in the limited flight history category, and then finally if you've flown a lot you get put into the significant flight history category and the requirements to get in there just keep going up once you get there.

The reason nasa does this is they want to both encourage additional commercial providers to develop launchers and they want to make sure that their most important missions go on the launch systems that are the most reliable ones so from the nasa perspective if i'm a program in nasa and i need launch services, they will do what's called a payload class evaluation, and class a b c and d are the simplest ones and nasa calls them high risk. What that really means is they can accept high risk, so they're saying this program we're willing to accept launching on a rocket with no flight heritage even though we realize that there might be a problem, and then as we get to the more important ones - the b and c ones - then you need at least some fight history before nasa will allow you to bid on that sort of thing.

Then if you get up to what nasa would call the flagship sort of flights - things like james webb space telescope, anything that people are likely to hear of - that will be payload class a and you need significant flight history to be able to fly that.

You can only bid on payload classes you're certified to carry and spacex currently has a certification for class A, so they can pretty much fly everything so that means if you want to compete with spacex for launching nasa payloads you need to be able to fly enough to get into that significant flight history, or at least if you want to compete with all of those flights

The next topic is looking at fixed costs and how that relates to your flight rate. Every launch company has fixed costs - you need a factory where you build rockets, you need some sort of launch pad you either own or lease, you have a recovery fleet if you're doing reusable rockets and then you have the salaries for all the people for engineering and operations.

You need to figure out how to pay for these and you need to pay for these if you fly once a year and you need to pay for these if you fly 20 times a year

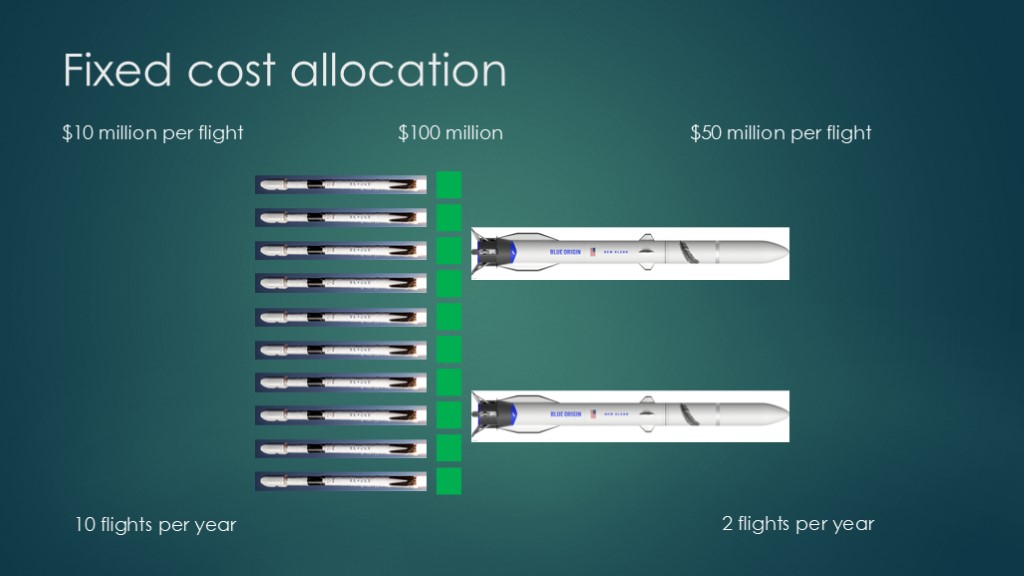

Let's assume you're in a company and your fixed costs are about 100 million dollars a year, and let's further assume you're doing a new launcher and you think initially you're going to fly a couple times a year, so what does that mean?

Well that means the amount of fixed cost allocated to each flight is 100 million divided by 2 or about 50 million per flight. If you think of this from a profit perspective for each of those fights you need to pay for the rocket, you need to pay for the 50 million, the part of the fixed costs allocated to this launch, and once you've done that then you can pay for profit. What that means is these fights are going to cost a lot because you aren't flying very much.

If for example you're at a company that flies 10 fights per year, we're able to spread out that fixed cost across far more flights, so 100 million, 10 flights, 10 million per flight, so very basically the more you fly, the less your fixed costs apply to each launch and the less you can charge for each launch.

This makes it very useful for an existing launch provider who flies; they already know what their fixed costs are and if they fly a lot, they can allocate them across a lot of flights.

If you're trying to be a new company you have to try to spread them across a relatively small amount of flights and that limits the amount you can charge or i guess that actually increases the amount of charge

The next topic i'd like to talk about is what's called the first mover advantage, and first mover is really really misunderstood.

The concept of first mover is that if you are the first company to go into an area, you end up with this advantage but being first is not an automatic advantage.

Being first may give you opportunities to take advantage of the market opportunities that exist now and those market opportunities will not exist for later entrants, so by being first i can get an advantage now,

It may not be a durable advantage but it may also give me a chance to establish moats, so just in the very obvious case it may give me a chance to work with a specific set of customers and establish them as regular customers.

Now can other people take those customers away?

Well, definitely and the ability of them to do that depends on all the other factors that i'm talking about.

First mover does apply in the case of spacex and i want to do that by talking about the launch markets that

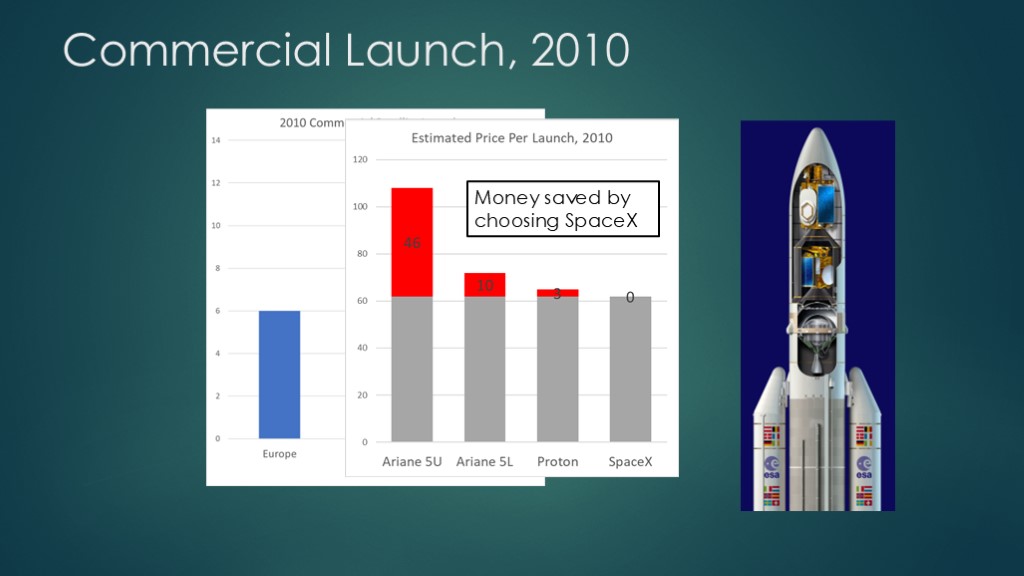

What did it cost to launch in 2010?

These are rough estimates - all the numbers i show you are going to be rough estimates but they will get the basic idea across the arion 5; upper berth it's about 108 million and the lower one is about 72 million. That's probably not exact but that's probably in the right ballpark. Proton about 65 million and spacex was a firm number - they actually published their number and said we'll launch your satellite for 62 million - so what we see is that spacex is fairly competitive with proton and they look pretty good compared to ariane.

I'm going to add some coding to this chart and basically what these numbers show is the money you could save by choosing spacex and what we see is if you were going to fly proton you'd save a little bit of money by choosing spacex. If you're going to fly ariane as the lower payload you'd save a fair bit of money flying spacex, and perhaps more importantly you wouldn't have to do all that excess design work and you wouldn't have to coordinate schedules so that you launch with the upper one so that is a little more convenient, and if you're going to fly arion upper stage the upper berth you could save quite a bit of money by going with spacex assuming that spacex could handle your satellite, so this is the reason that spacex generated so much business so quickly when they started with falcon 9 it only took them a few years and they were launching a lot of satellites.

Now part of that was they were considerably cheaper than arianne, part of that was proton has never been a particular particularly reliable launch system and about this time they had some significant reliability issues so spacex managed to take some business from proton that they might not have in other circumstances and the other thing that was going on was there was actually more demand for launch than the existing providers were able to meet, so you kind of put all those three together and that is the way that spacex managed to essentially start launching a lot of satellites very quickly and the point for talking about this is that that particular market condition only existed in 2010.

If you're trying to go into commercial launch in this same market now you have to compete against SpaceX.

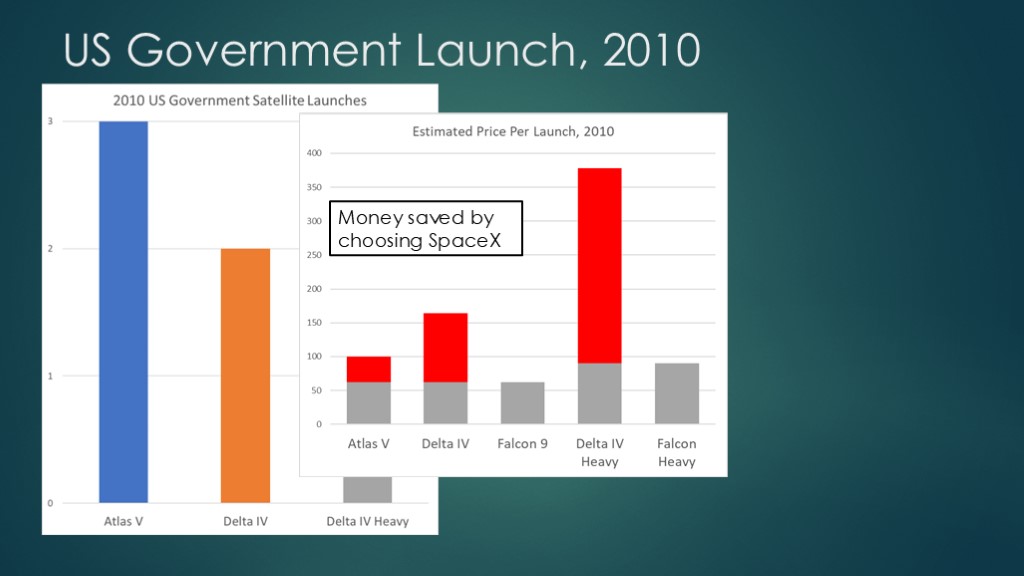

In 2010 there were six us government satellite launches three by atlas, two by delta four and then one by delta iv heavy.

All three of these vehicles are operated by united launch alliance and at that point united launch alliancehad a monopoly essentially on this sort of government launches at

least on what we'd call nssl now - it was called eelv the previous program - so launching things for the department of defense ula had a monopoly.

So what did these ones cost? These are also hard numbers to get so don't take them as verbatim or as necessarily true but they are in the right ballpark, so atlas 5 about $110 million. Atlas 5 uses an approach where they have a base system, a base launcher and then to get more capability they add solid rockets to the outside so that means you aren't always at 110 - you might be 110, you might be higher.

Delta 4 $164 million it also uses that solid rocket boosters added. You can think of those as competing with falcon 9 at $62 million.

If we look farther over we see delta 4 heavy which is $350 million - perhaps even more than 350 million - a very expensive rocket and that roughly competes with falcon heavy which is about $90 million. Of course falcon heavy didn't exist in 2010, but you can look at that number compared to now i guess.

If we add in the color coding what do we see well we see once again there's a lot of money that could be saved by choosing spacex. Now the department of defense is notoriously not terribly price sensitive when it comes to launch - they're actually much more concerned about reliability than they are about money - so instead of looking at this and looking at those numbers as money that the department of defense could save, you should look at it as margin that spacex can use to increase the cost of their bid.

So you can see if you're competing against atlas 5 you can push your push your bid price up. If you're competing against delta for heavy launch you can push your bid price up a lot and you'll still be cheaper so these ones. Unlike the commercial ones, the commercial ones have gone away, because if you're trying to launch commercial you're going to be competing with spacex. Here it's a little different because ula still has half of the contract here so they are still trying to fix this

Summary on first mover.

In the commercial market spacex was cheaper and they had some other market conditions that made it easy for them or easier for them to gather a lot of business. In the us government market spacex could charge a premium above their commercial price and still get business because they were so much cheaper than the existing solutions. These are the first mover advantages - the inefficiencies in the market made it easier for spacex to establish themselves.

If you're a new entrant you aren't competing with those high priced options, you're competing with spacex with a bit of a caveat - programs like nssl choose two providers so we have the relatively cheap spacex provider and we have the much more expensive ula provider and you could still be a new entrant and you can compete for this nssl launch and compete against ula now.

Note that ula has been doing this for a long long time and they are right in the process of building their new vulcan rocket and that will allow them to do all the launches they want with a single system - they won't have both atlas 5 and delta 4 heavy and that is going to reduce their per launch cost and it's going to reduce their fixed costs considerably so if you want to compete against them it's going to get harder than it was in the past.

Vertical integration is the next topic.

I'm going to talk about vertical integration only in the context of engines because I think that's probably the biggest impact but this applies with engines, it applies with valves, it applies with avionics, applies with pretty much any kind of

advanced system that goes into your launcher.

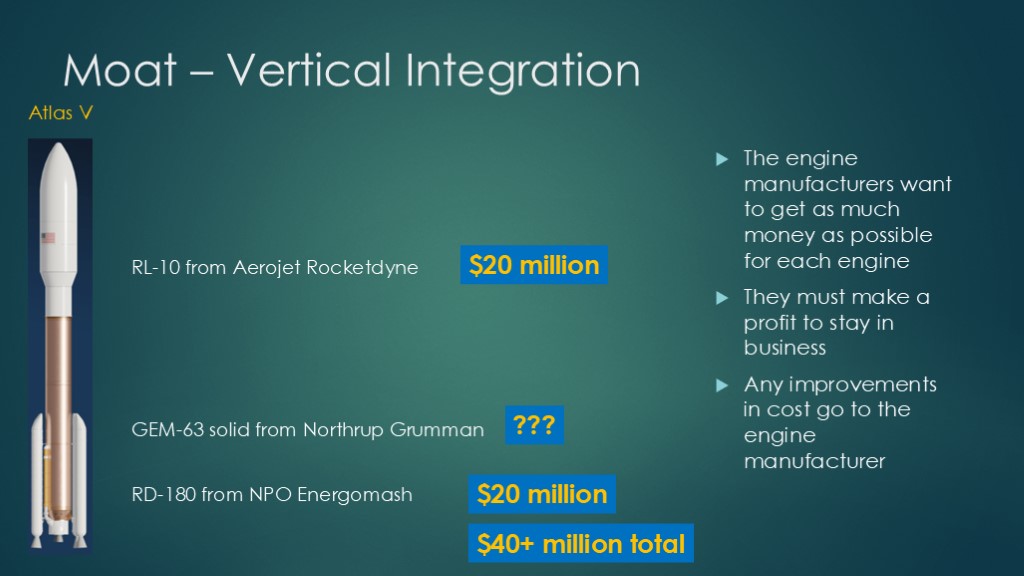

Go back to the atlas 5. Its base engine of the first stage is an rd180 from npo Energomash in Russia, and its centaur upper stage engine is an rl10 from aerojet rocketdyne. These are both wonderful high performance engines. As i mentioned earlier for some mission they will add on solid rocket boosters - they're currently using the GEM 63 solid rocket booster from northrop Grumman. I went and looked forprices on these and of course ula doesn't say what they pay for these so we just have estimates...

The rd-180s are estimated to be about 20 million dollars per engine, and the rl-10 is also estimated to be about 20 million dollars per engine.

I went looking for estimates of the solids and after i spent a fair bunch of time I realized nobody was talking at least publicly i about how much these cost and this is a new one. I also looked for the old solid they used to fly - I couldn't find any more numbers there so i don't know what it is - $500,000, a million, something like that.

So if we add these up uh we see the atlas 5 is looking at 40 million dollars for engines for any given flight and that is a lot of money and if you look at you know the everything else has to come out of that price so 40 million dollars.

And so the question is why are these engines so expensive and well, the simple fact is the engine manufacturers listed here want to get as much money as possible for each engine - that is their business and they need to make a profit to make

to stay in business.

Now because a vehicle like the atlas 5 only flies a few times a year they are only going to be buying a few rl-10s from aerojet and they're only going to be buying a few rd-180s so what does that mean? well that means the engine manufacturers need to allocate

their fixed costs to a small number of engines.

Now another factor going on is that any improvements in manufacturing will show up as profits to the engine manufacturer, they will not show up as cheaper prices to ula, and the rl-10 has been flying for more than 50 years now and clearly the people building it have had a lot of time to optimize their build process, so you can figure they are doing fairly well on it assuming that they're fine with their fixed costs.

So this is why these engines are so expensive ula would like them to be cheap but frankly aerojet doesn't have any competition for the rl-10 - the centaur upper stage is designed for an rl10. You'd have to build something else and as long as they keep making centaurs they need to buy rl-10s for pretty much for whatever they cost and there isn't really a lot of competition in the rocket engine realm anymore

There used to be - back in like 1960s and 1970s lots of people made engines and they've mostly been bought up and combined and merged so we're left pretty much with aerojet rocketdyne.

This is a case where ula does not have vertical integration - they need to buy their engines from somewhere else.

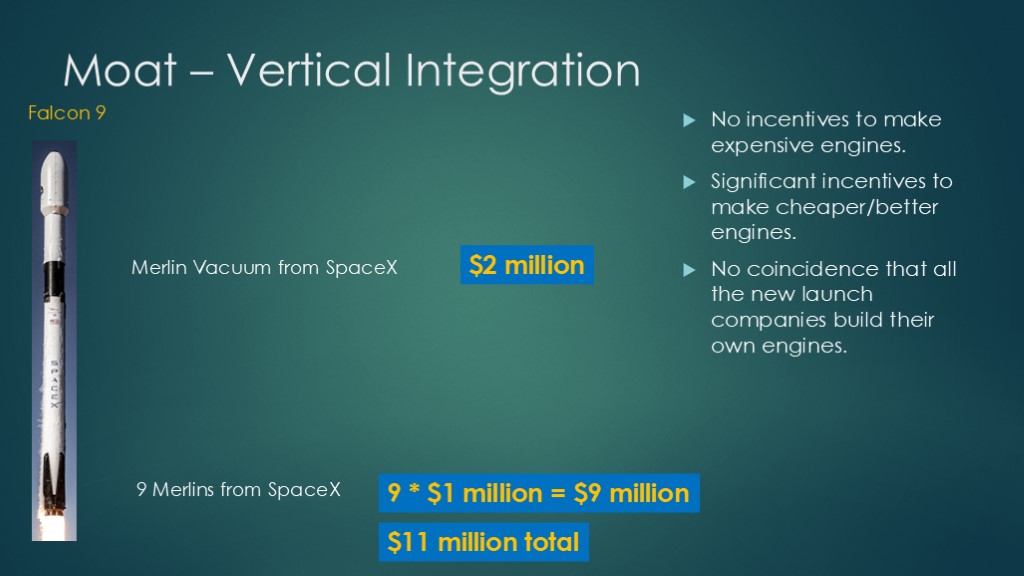

looking at the falcon 9 in the base it has 9 merlin engines and then in the second stage it has a merlin vacuum engine, and both of those are developed in-house by spacex.

we have guesses on what it cost based on some stuff musk has said - the base merlins are about a million dollars a piece. They're probably a little bit less but we'll say about one million and they have nine of them so that's about nine million in engine cost.

The merlin vacuum is a much more complex engine than the one used in the first stage. It's probably a two million dollar engine - something like that - so what does that give for our total engine cost? About 11 million, or well over 20 million dollars cheaper than what ula is paying for their atlas engines, and the reason is what very simple. The spacex internal engine team has no incentive to make expensive engines and they have every incentive to make cheaper and better engines so they want to make them cheap so the engine team goals align with the rest of spacex's goals, and that is the advantage of vertical integration.

So it's really no coincidence that all the new launch companies build their own engines; if you look out rocket lab builds their engines, blue origin is building their own engines ,all this sort of stuff happens simply because it's much much harder to compete and it's especially much much harder to start up a company if you buy engines

Another moat around engines is simply engine creation - I usually just say engines are hard - it takes a long time to develop them - you need factories like the Blue origin factory on the right, you

need test facilities - that's the spacex test facility in mcgregor texas on the left - and you need an experienced team.

So if you're trying to compete with spacex who has years of engine development you need a team that can compete in engine development, so it's going to take you a while to create that team.

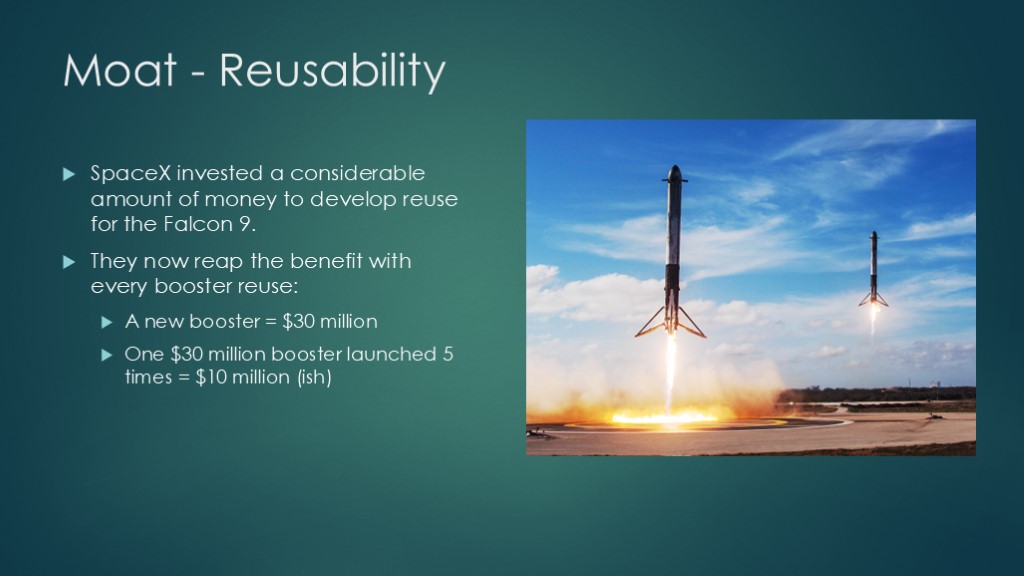

Reusability

This one seems fairly obvious... Spacex invested a lot of money in developing reuse and they now reap that benefit every time they fly a booster. So if we estimate that a new booster is about 30 million - it's probably in the right ballpark - so if we fly a new booster every time back before they were reusing boosters it would take 30 million dollars - that was 30 million dollars in their cost

If you take that same booster and you can launch it five times, that's about six million dollars of cost allocated to each of those launches. Now you have to go and recover it - you need to bring it back, you need to inspect it, you need to do some refurbishment and I just threw a number at this it takes your costs probably up to around 10 million, and it might be 10 million it might be 15 - I don't know what the exact number is but the important point is it's much cheaper to refly boosters than to build new boosters

If you're a competitor and you don't have reusability you're going to find it hard to compete, so spacex has somewhere between a 10 to 20 million dollar advantage per launch merely because they can reuse these boosters.

The last moat i want to talk about is related to people and this one i think is really not understood very well.

There seem to be a lot of people who think that engineers are just kind of interchangeable and if i want to start up a new project i just need to find some engineers and they will perform about as well as any other engineers.

And this partly depends on people and it partly depends upon the environment in which they are working. There's this great book by daniel pink called drive which is all about motivation and i'll summarize it.

Pink's theory is that there are three big things that motivate people and the first is autonomy and this is i get to decide how to do my job - i can be self-directed. The second is mastery - i can get better at what i do i can develop my skills. and finally purpose i work on something that is important and that gives us meaning and that gives us contribution.

So these are the things that actually drive people, especially when they are engineers and they're going to be getting paid a fair bit of money -money is much less of a driver. So if we look at spacex, spacex is notorious perhaps for providing all three of these to their young engineers. There's a nice video that talks about pink's drive and some of the evidence so go to youtube and search for it.

So spacex is great at providing autonomy, mastery, and purpose and its employees value these three things over things like work life balance - it's very well known that if you go to spacex and work you're not going to have a lot of free time - you're going to spend a ton of time working. The people who go and work there choose to do that because of these other things so essentially spacex by doing this gives themself a nice way to attract these sort of people - they have a recruiting advantage on the sort of people who do well in this environment.

Another way to say that is they have first call on new graduating engineers who really want to do this kind of thing and this kind of thing is exactly what you need to build a new company when you're trying to compete with spacex.

you can look at all of that nice web streaming that spacex does as a pr thing, purely to recruit people to come work for the company, and that's why - it's very obvious - most of their online hosts are young engineers, and clearly very knowledgeable and very passionate engineers. So merely by producing their web streams in the way they produce them they reinforce that spacex is a place that those kind of people want to come and work.

Now having said that, this is the sort of advantage that can go away easily and it could be a case where spacex just stops hiring people, they stop expanding, and it could be that something inside happens and the corporate culture changes and these three things that are motivating people go away and people start leaving spacex because they've lost these things, so this would be something to watch, to understand why people are leaving spacex.

so that's pretty much what i wanted to cover the big point is the large aerospace

companies like boeing like lockheed they aren't competing with spacex

because there are too many moats it's not worth the investment to try to

cross them you can look at the problems it would take what would it

take for ula to become competitive and that would take a bunch

bunch of money for them to do that and then they would just be competitive but

they might not actually get more contracts than they are currently getting

national governments are an exception so we see efforts in europe

to try to do something similar to falcon 9 and part of that is national pride or i guess

national pride for many companies for many countries part of that is trying to get back

some of their competitive advantage and then we see it in china also very

much a national national pride sort of thing small and new aerospace companies will

try to compete with spacex simply because that's what they need to do to grow and we see that we see rocket

lab has announced they're building a new launcher called neutron which is kind of like a smallish

slightly smaller version of falcon 9. and they will have problems with these

spacex moats they expect that there's enough new business in

big constellations to keep them in business and they also expect that they can be cheap enough

because they're already a very small lean company kind of like spacex to be able to compete

there will also be a chance for a company like like rocket lab to conceivably start

competing in contracts like the nasa resupply ones

and maybe even in the nssl ones and since those contracts are not winner take all

they don't have to compete with spacex they just have to compete with the next best company

starship which i didn't talk about at all will work will clearly make all of this harder assuming starship is

successful and i think that's another thing that's pushing these big

companies uh to not invest

so that's my talk i hope you enjoyed it

English (auto-generated)

AllFor youRecently uploadedWatched

That's pretty much what i wanted to cover.

The big point is the large aerospace companies like boeing like lockheed they aren't competing with spacex because there are too many moats - it's not worth the investment to try to cross them. You can look at what would it take for ula to become competitive and that would take a bunch of money for them to do that and then they would just be competitive, but they might not actually get more contracts than they are currently getting.

National governments are an exception so we see efforts in Europe to try to do something similar to falcon 9 and part of that is national pride for many countries. Part of that is trying to get back some of their competitive advantage and then we see it in china also - very much a national pride sort of thing.

Small and new aerospace companies will try to compete with spacex simply because that's what they need to do to grow and we see that we see rocket lab has announced they're building a new launcher called neutron which is kind of like a slightly smaller version of falcon 9. They will have problems with these spacex moats but they expect that there's enough new business in big constellations to keep them in business, and they also expect that they can be cheap enough because they're already a very small lean company kind of like spacex.

To be able to compete - there will also be a chance for a company like rocket lab to conceivably start competing in contracts like the nasa resupply ones and maybe even in the nssl ones, and since those contracts are not winner take all, they don't have to compete with spacex, they just have to compete with the next best company.

Starship which i didn't talk about at all will clearly make all of this harder assuming starship is successful and i think that's another thing that's pushing these big companies to not invest.

So that's my talk i hope you enjoyed it